As part of the Seminar on Public Engagement and Collaborative Research’s collaboration with community partner Danspace Project, GC PhD candidate in Theater, Janet Werther, has worked in archives at the Houghton Library at Harvard and the New York Public Library to study the life and work of the dancer John Bernd. This research has been in preparation for Platform 2016: Lost and Found, a multi-faceted curatorial Platform at Danspace, curated by Ishmael Houston-Jones and Will Rawls, which is currently ongoing and includes a series of public events at the Center for the Humanities: Interventions in Narrativizing the AIDS Crisis and A Matter of Urgency and Agency: HIV/AIDS Now. Janet and I discussed the work she’s done on Bernd, which led to a conversation about the legacies of caring labor in the wake of the AIDS crisis, how the content of dance changes in relation to who’s dancing, dance as a life practice, and the connections between archival work and caring labor.

An Introduction

Jordan Lord: Could you introduce John Bernd to readers who are not familiar with his work? What drew you to him? What have you found in his archive?

Janet Werther: I should begin by stating that, for many people in the experimental, “downtown” dance community, John Bernd was the first dancer they knew to become sick from HIV/AIDS-related illness. He became sick in 1981 and survived until 1988. John kept making dances throughout his illness, performing at the PS122 Gala in 1988, just months before his death. John Bernd was a college-educated cisgender white gay man who had moved to New York City from the American heartland.

The Danspace Project Platform is not centered around him because he “fits the profile” of the most visible people with AIDS in New York City during the initial crisis in the 1980s and 90s but rather because he was part of a tight knit community, a community that danced with him and cared for him. Ishmael Houston-Jones, one of the curators of the Platform, was close friends with John, danced in several of his works, and formed an important part of John’s caregiving collective as his illness progressed.

So while the curatorial team has worked very hard to problematize the perception that there was a “typical” profile for people with AIDS who looked and lived much like John, part of what this Platform is doing is passing on a legacy of very intimate experience to people in my generation, and John was/is a crucial part of that. I feel like I’ve gotten to know John Bernd pretty intimately myself through my archival work, by watching videos of his dances, and in talking with people who knew him well. I am incredibly grateful to Ishmael for introducing him to me.

In terms of his work, I think that for a long time Bernd wanted to find a way to be process-oriented and experimental, He studied with Sara Rudner, who was my mentor, actually. From really early on in his archive and his papers, Bernd talked about the influence of Rudner on his practice and work, especially her teachings about how one work extends into one’s life and vice versa

John found his way to the PS 122 crowd, which was just burgeoning. He was curated onto a split bill performance with Tim Miller, by Tim Miller, who was interested in him sexually as well as artistically. Bernd became really involved in the early Open Movement sessions at PS 122, which, from everything I understand, was the early heyday of that organization.

They rotated who taught class to the group, and there was a sense that everything was possible. This community had some still-legible faces--Yvonne Meier, Jennifer Monson, Ishmael Houston-Jones. And John was a big part of that community.

Living & Dancing With AIDS

Janet: As I mentioned before, John lived with HIV/AIDS from from 1981 until 1988.To be able to live that long with the disease was pretty gargantuan for the time. And he continued to make work that entire time. The Foundation for AIDS Research states that by 1982, of the 771 reported cases, there were 618 deaths, so people were dying very, very quickly, and the same trend continued throughout the 7 years Bernd lived with the disease

In 1982, John made the piece Surviving Love and Death, which is about his breakup with Tim Miller and his diagnosis. He made a blender’s worth of food and medication onstage in that piece. He also made a beautiful, “abstract” dance phrase with the movement mirroring the relative movements of his platelet count during the initial onset of the illness.

Also in 1982 at Danspace Project, he debuted the first in a series of dances called Lost and found (scenes from a life), and there were three parts to that. Part 1 was a work-in-progress, Part 2 was sort of his gesamtkunstwerk, which included big dancing, a video projection of still life from the city, great art works, male nudes, and chanting à la Meredith Monk (who he had performed with in Quarry). Part 3 came after he had been in the hospital and included some of the people who were his friends and caretakers improvising together.

There was this really difficult series tensions toward the end of his life between wanting to have some kind of spiritual awakening that would heal him, wanting to finish his life’s work before he died, and wanting to keep making work because there was a sense of value in/for himself that he could best understand by making art.

That sense of purpose was supported by some of his friends, while other friends wished that he would just convalesce. There was also the fact that he was in and out of the hospital and needed the money that he could get from continuing to produce work. He could no longer maintain his day job, but he was getting grants, so making dances was his only means of income for covering his medical bills and paying rent. His friends helped him fill out the paperwork for Medicaid and disability, and there are letters in the archive from people saying basically, “I understand that John Bernd applied for a grant through your organization. He may not have told you this, but you should know he really needs that money. He’s sick; he needs it for medication.” On the one hand, Ishmael still has a check to John from the NEA that was never cashed. People made sure that he had a roof over his head.

But on the other hand, there’s a piece of mouse poop on a page in one of his notebooks in the archive that I think speaks to the conditions he was living in at the end of his life.

The pressure to produce is a part of that story that I’m still struggling to grapple with, along with the ethics of that reality. I don’t know if we’ll ever really know what was best for John or what he most wanted or what he needed. Everyone comes at a question like that from the perspective of what they presume they would want, whether that’s to keep working or to be able to not work. So just like his spiritual forays into the desert did not save him, and just like continuously drawing the temple he saw in a dream did not save him, making work did not save him. But not making work wouldn’t have either.

Release Techniques & the AIDS Body

Jordan: You’ve been able to construct an understanding of Bernd’s work through the archive in a way that no one else, who didn’t have access to all of this material at once, could have. And when we talked before, you mentioned that, instead of reading certain formal aspects of his work abstractly, you are reading content into them, particularly in terms of how Bernd was using “release technique.”

Janet: It was fascinating to speak with Yvonne Meier about this, too, because she was the one who brought Skinner Releasing to Open Movement at PS122 and started teaching it in New York. John studied with Yvonne outside of Open Movement as well, and it’s clear from his archive that it became very important to him to identify as someone who had a regimen of training through release technique.

The sort of ideology (if I can use such a word) behind releasing is that using the minimal amount of effort possible to do a movement is the most efficient way to do it. The thing you’re doing might be very effortful, but you don’t use more effort than you need. I think there is something really full to consider in thinking about releasing not as aesthetic training techniques but as techniques that help to heal and retrain your body without taking time off from moving and performing.

I first noticed this in John’s work while watching an excerpt of Two on the Loose, which was his last performance, with Jennifer Monson. They performed this excerpt at the PS122 Gala in 1988. In the video, Jennifer is young, and she is obviously very muscular, very powerful. John sort of forgets where he is at some moments, and she simultaneously leads and follows him. Everything is very line oriented. But it’s a different kind of line. That was the first dance of John’s that I watched. Then I looked at his oeuvre in chronological order. It’s fascinating – Lost & Found Part 2 is the first time that he starts to look sick on stage. And yet he is moving so much more efficiently than the other dancers. I associate that with releasing and, aesthetically, it looks like releasing.

When John was feeling better after the initial onset of his illness and able to dance again, he went into the studio and sort of let himself out of a cannon, and he injured his foot right away. That was a real moment of “ahh I feel better, and I want to dance, but I can hurt myself.” Yvonne Meier also came to releasing through an injury. Alexander Technique, which is another form of release technique, was coming into the community because Trisha Brown had sustained an injury and was studying it as a healing practice for herself.

What’s fascinating is that, in talking to Yvonne, it seems that releasing and the AIDS body maybe never came up in direct conversation between them. So I feel like sort of an investigator here in terms of finding out who else that had HIV or AIDS was studying release and who, if anyone, was talking about these connections. Releasing was sort of coming into the community at this time in the eighties, but nobody was talking about it around AIDS, which I find fascinating.

Jordan: Hearing you talk about it, what I find kind of amazing is that releasing could ever, then, not be read in terms of content and especially in terms of this idea of convalescing and moving at the same time.

Janet: Yeah, so when you look at him, and he’s obviously close to death, that’s an absolute necessity. If he expends more energy than necessary on any given movement, he will not be able to keep moving.

Meanwhile, since then, releasing has become this kind of aesthetic marker of “downtown experimental dance” in a way that’s generally read as abstract. I’m invested in recovering this question of how and why releasing took off at this time, who was practicing it, and why someone like John would have been really drawn to it. Because I think even if you’re dancing about “nothing,” there’s obviously content in the idea that you’re dancing while your body is terminally ill, and this technique is what’s keeping your body dancing as efficiently as possible for as long as possible. The stakes were extremely high for John. And I don’t know how showing a video of his work would read to for someone who’s never heard of him or doesn’t know anything about his life circumstances. But as he gets sicker, it’s clear that he’s sick, and one way or another, that’s in the work as a part of the work.

Caregiving, Archives, and an Archive of Care

Jordan: Another aspect of your research that you’ve talked about is how, as John got sicker, his work turned to include the caregivers in his life.

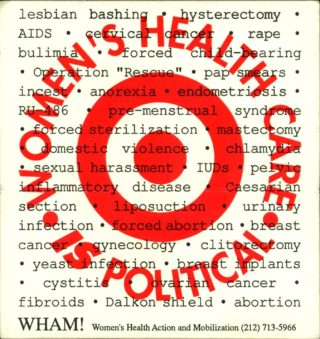

Janet: Yeah, it’s fascinating. At first, he made solo works. He made duets with Tim Miller. He made groups works, small groups works with men. He made more solo works … and then all of the sudden he starts working with women and, primarily, with lesbians.

At the very end of his life, Bernd worked with Jennifer Monson, who was a young person moving to the city, looking for people to dance with. She made her way to PS122 and she and John found each other. Jennifer became both a caretaker and a performer. In Lost and Found Part 3, Yvonne Meier and Stephanie Skura performed with John along with Ishmael Houston-Jones, who was healthy and also became one of his caretakers and continued to work with him. Lucy Sexton was also one of his caretakers. As women appear in his dance works, they are also people who are caring for him. So for Bernd, there was no separation of life and work. I don’t know that there could have been for him. In talking with Yvonne about being in his work toward the end, she mentioned that being a performer for John also became a kind of caretaking.

Collectivity became really important for John, and I know, last time we spoke, we were talking about the fight for marriage equality and how that comes out of the AIDS crisis--people wanting to have had survivor benefits, wanting to have had hospitals and next-of-kin rights over funeral arrangements and things like that. But John’s legacy is held by a collective of five people. Marriage equality would not have helped him. And maybe it would have been a different story if the person he had been in love with was a different person or if they had still been a couple at that time. But it was really the collective that was his group, his family.

Jordan: When we spoke last you also mentioned the fact that care providers were the ones primarily responsible for preserving these archives of works by many artists who died at this point in the AIDS crisis.

Janet: Things that might never have been archived were archived because there was no time to sift through and decide what was worth keeping and not worth keeping. It was thrown in boxes and given to whoever would take it.

Also, these guys were young. So determining whether or not their work would have had long-term resonance is impossible. We don’t know. We can see how Yvonne and Ish and Jennifer have continued to shape the field. John was earning grants, so that’s significant. We can assume that he would have continued to be important in the field. On the other hand, Fred Holland, who recently passed away (rest in peace and power), was also an early collaborator of Ishmael Houston-Jones’ and he turned to sculpture and stopped performing. Fred’s impact on dance is through Ishmael’s early work. So we can’t really know what the legacy might have been for someone who was in their early thirties or forties when they died if they hadn’t died. This work of building archives was largely: this person died; they were an artist; box it up; put it in an archive.

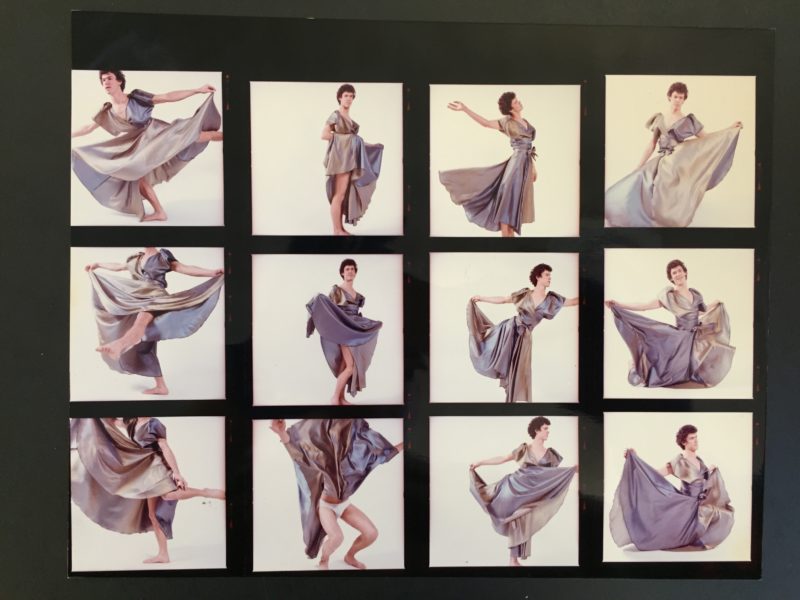

Parts of the archive are a mess. The last box of John’s is all the stuff that was active for him when he died, like the notebooks he was writing in. There was a contact sheet of photos that was getting ruined, and I knew from looking through the entire archive what piece they’re from. I know what folder they belong in, and it’s an effort now trying to work with the archive to re-catalogue that particular item because it’s not in the box it belongs, but the box it belongs in is harming it.

John’s is not an archive that is very carefully tended to. There are a lot of materials at Harvard, and there are a lot of materials at Harvard that I’m very, very invested in. And I’m very grateful that Harvard took John’s papers. Maryette Charlton was a lesbian whose son Kirk Winslow was a photographer. Kirk collaborated with John and also died of AIDS. Maryette gathered up a bunch of people’s stuff and I guess she had some connection with Harvard, so that’s how John’s stuff ended up there. There’s a book called How to Make Dances in an Epidemic by David Gere. That’s the major work that has been done on this community, and John is in that book. But that’s the primary art historical reference to his work, and I don’t know that people are going up to Harvard regularly to look in his archive.

The Downtown collection at NYU is a totally different story. It’s very curated and tended to, and people know exactly what is where. But it’s not an individual’s papers in the same way. There’s a lot at the New York Public Library that they’re still sifting through, and there are some efforts toward make people aware that they have as much as they do and toward getting people to access it. But it feels really different to go into an archive like John’s at Harvard and get to know the individual artist and the work really, really well and then to be communicating about the care of the archive than researching someone who died at a ripe old age and who everyone knew was important for that reason or another, whose stuff was carefully collected and curated before it was ever given to an archive.

Jordan: You’ve also talked about how you’re thinking about your practice as a form of caretaking and an extension of these caretaking practices around Bernd.

Janet: There are things that are really material about that, like trying to get things labeled properly and put in the right folders. And then there are things that I think are more immaterial but no less important. For example, everyone in the downtown New York dance scene can speak to the fact that we are living in the legacy of Judson Church. Everyone knows that, and we are all functioning collectively under that premise. But a lot of people don’t know John’s work.

It’s one of the premises of this platform at Danspace, that there’s a legacy that exists. It’s not only that these people are lost; part of it--at least for me--is the surprise of how much the legacy is not lost, just unnamed and unnoticed.

I think release technique goes in that category. The people that are still alive from that era, and there are many people, have been passing down whatever they have in their bodies. Dance gets passed on body to body. But AIDS is not something that’s often talked about in the dance community anymore. It’s something that we sort of “know,” as in we know that it happened. There’s Dancers Responding to AIDS. But, in general, people are not in class and teaching techniques by saying “this improvisatory practice developed for me while I was working with an artist who was dying of AIDS.”

The improvisatory practices, the abstract and experimental practices, the physical practices that we’re still working with,at the very least, were developed through that period. That’s to say, these practices didn’t originate in AIDS but were mutually affected by AIDS.

So part of the caretaking feels like shining a light on what’s already there both in terms of the legacy of work and the context from which it was emerging. We’re doing these dossiers on not only John but several people, and part of the idea of the dossier is that you can be “introduced” to the artist quickly, but that it’s also a way to know where to go to find out more. And then hopefully, when you get to the archive, at that point, people do know what box the thing you’re looking for is in, and it’s been correctly catalogued.

I want to be super clear that I’m so grateful to every library and archive that took in this material, that didn’t judge whether or not it was “professional” enough or whether or not that person’s legacy was going to be strong enough. I’m so grateful that the material is there. And libraries and archives are so underfunded that, if nobody is coming to see these boxes, of course you’re not going to spend extra labor on them. But it feels like caretaking because otherwise those boxes are just collecting dust.

(I want to add here that since this interview, I’ve begun reading Ann Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings, and her work has helped me continue to formulate my perspective on caregiving and archival work.)

Jordan: You’ve also talked about the caregiving that happens in trying to reconstruct this story and trying to bring out how the crisis affects caregivers.

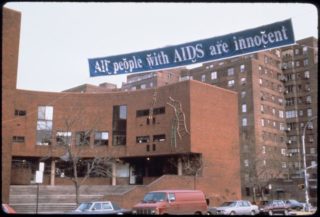

Janet: I think that our public discourse on PTSD has gotten really strong in terms of war. But people who have lived through the AIDS crisis have also lived through a war, and it can be really hard for people to talk about it.

There are certain ways of listening that become really important. You go into a conversation expecting to ask a particular question, and someone takes it to a totally different place. Maybe your question is just not going to be answered, but you go with them, and then they’re talking about something else that’s super important, that you didn’t even know to ask.You sort of have to follow people on their remembrance journeys.

I think there are a lot of people who want to talk about it, but it’s very hard. There are things that people don’t remember or don’t realize that they remember. It seems like everything was just going so fast. Dates get confused sometimes.

I also think there is a lot of interest, a lot of curiosity. People of my dance “generation” imagine and hypothesize what they can’t get directly. But we also really earnestly want to know and to be sensitive to something so enormous that we didn’t experience. Then, as artists, what do we do? We make art. So it becomes, “can I have this conversation with you about this traumatic experience so I can use it as source material for my art?” I don’t blame people for doing that at all, by any means, because I think that people are coming from a really earnest place and have really sincere interests. But it feels good to be in a position where I can ask people to share those stories and not be making art about it.

It frames the ways in which I look at writing about this. I don’t want my writing to become just another kind of cultural production that I have vultured unintentionally to make a name for myself as an academic. I am actually trying to write about these processes, about the ethics and politics of what it means to do this work. I want to be really sensitive to that trauma. And I have to say I’m feeling very tender about it today. I, by no means, want to co-opt someone else’s pain, but the more that I feel like I know John or the more that I know about people’s stories from that time, the more emotional it is for me also.

There are things in the archive that every time I mention--for example, John’s twenty-seven-plus page letters to Sally Banes that we’re not sure he ever sent or didn’t send-- people are like, “What? He did that? I had no idea!” There are things that I know intimately about him that even his dearest friends don’t know. But there are also things that never existed on paper or on film or video.

There are fissures in my knowledge of John that I couldn’t have even known were gaps until I was having this specific conversation with another person who was there at that time. So they’re an archive, too.

--

Please join us on November 10th for "A Matter of Urgency and Agency: HIV / AIDS Now," part of Danspace Project's Platform 2016: Lost and Found, a conversation that will focus on current activism and historicize contemporary issues related to HIV / AIDS, along with strategies for archiving and theorizing the present.