As a follow-up to the public discussion #SaySomething, The Problem with Kindness: What Should Educational Leaders Know, Dr. Terri N. Watson speaks with her former student Dr. Gina Charles, reflecting on their relationship and the importance of Black women teachers for Black girls.

--

Dr. Gina Charles: I am a product of New York City’s public school system, and I was fortunate enough to have Black female teachers and mentors who invested in me. Dr. Terri N. Watson was one of those teachers turned mentors. She was my 7th grade English teacher at Junior High School 45.

When I first met Dr. Watson, I was completely enamored by her presence. How old is she? What products does she use in her hair? She looks like me and dresses well. My young mind registered all of these things, as she introduced herself for the first time to the class. Prior to this, I had not encountered any young Black female teachers at my inner city school that looked like me, so seeing her was a welcome surprise. She was confident, poised, and always present in the moment. I wanted to acquire all of these traits and more!

Dr. Terri N. Watson: I began my teaching career in the fall of 1994 at Junior High School 45. I chose to teach at 45 because I knew that I would encounter children, Black girls in particular, who may need me. Moreover, I wanted to be whom I needed when I was in middle school.

GC: My name is Dr. Gina Charles, and I'm a board-certified family medicine physician. I was born in Dominica, West Indies, and immigrated to the United States when I was five years old. I grew up in a single-parent household in pre-gentrified Harlem with my brother and mother. It was there that I met Dr. Watson for the first time, and it was there she changed my life for the better.

Dr. Watson introduced our class to the Black literary greats, most notably Toni Morrison and her celebrated work, The Bluest Eye. She taught us that one must dissect each chapter in order to capture every nuance and symbol within the text. This was my introduction to critical thinking. In many ways, the girls in our class could relate to the story's protagonist, as she too faced similar struggles: growing up poor and Black and feeling invisible in her community. What I did not realize at the time was that Dr. Watson presented the material as a metaphor similar to our own collective ontogeny.

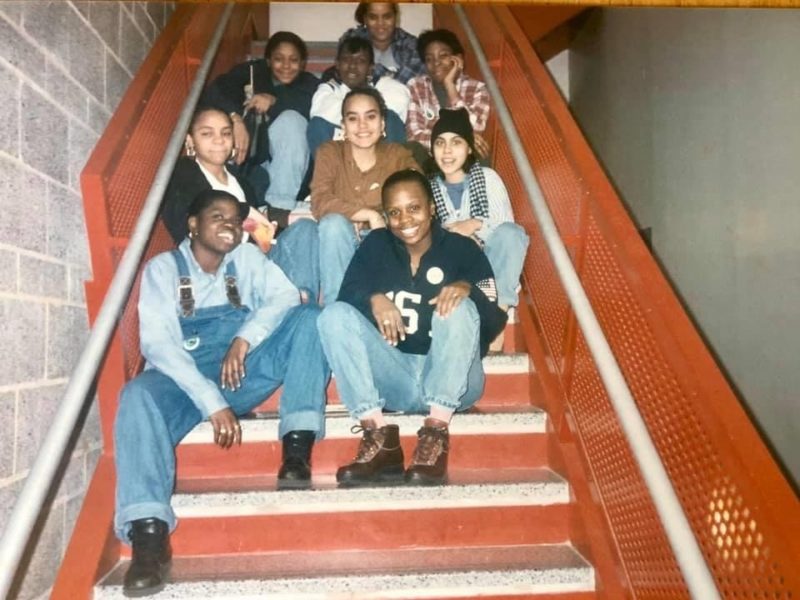

After class, my friends and I would spend a great deal of time conversing with Dr. Watson about our lives outside of the classroom. She made us feel safe, heard, and cared for. Secretly, I believe those sessions were as cathartic for her as they were for us. When Dr. Watson learned that one of my classmates was displaced from her home and placed into a group home, without hesitation, she brought her food and clothing. She encouraged my friend to keep attending school in spite of her bleak situation. Collectively, my friends and I never experienced this level of care from a teacher.

TW: Like many of NYC’s public schools, 45 was understaffed and underfunded. During my first faculty meeting I learned that I would only be allotted enough funding to purchase one set of novels for my students. I thought deeply and decided that Toni Morrison’s first work, The Bluest Eye, would be our shared text. I wanted my students, especially my girls, to see themselves and to know that they could write their own stories. I wanted them to know that I too was once where they were and that any and everything is possible.

GC: For many of us, Dr. Watson acted as the teacher, mentor, and big sister we needed at that moment. Her presence, words of wisdom, and encouragement made a difference for me. She possessed a specific type of cultural capital that she used to tap into students’ experiences. Because of her, I was able to avoid truancy and many of the pitfalls my peers succumbed to in middle school and later in life. One of my greatest takeaways from Dr. Watson is that one should always examine any situation critically.

By the time I got to high school, I was well aware of the world and my place in it. I knew I wanted more. I began to critically read the works of Zora Neale Hurston and devoured even more texts by Toni Morrison. I became captivated with the Black American experience: specifically the narratives of strong women. I can tell you with certainty that those texts helped shape my advocacy for women in medicine. Similarly, I made it my duty to be educated by Black female teachers who would challenge me. I went on to attend Stony Brook University and majored in Health Sciences/Pre-Med with a minor in Africana Studies. While there, I forged meaningful relationships with Black female professors who generously poured into me.

TW: I too am a product of NYC’s public school system. I was blessed to have a Black female teacher when I was in the third grade. Her name was Ms. Sams, and while she sometimes laughed at my jokes, she took her job seriously and demanded that I not only be good––she made me believe that I could be great. Ms. Sams was transparent, knowledgeable, and maintained high standards. While she is no longer with us in the physical realm, she remains my guiding light.

GC: There have been several research studies that demonstrate how racially matching Black students with Black teachers benefits the students. One particular study from Johns Hopkins found that Black teachers are more likely than white teachers to think a Black student will graduate from high school and earn a college degree, especially if the Black students are male. Furthermore, a 2016 Vanderbilt study showed that Black students are about half as likely as white students to be placed on a "gifted" track, even when they have comparable test scores. This disparity was challenged when Black teachers assessed Black students.

If we want to see a world with more Black women in leadership roles, we must take on the task of nurturing future leaders. - Dr. Gina Charles

TW: Black girls need teachers who believe in them. Teachers who see them for who they are––and who they can be. Too often, Black girls are stereotyped and placed in caricatures of Black girlhood that will never serve them well. These paradigms stymie their progress and stunt their growth. Hence, teachers must provide mirrors and windows that allow Black girls to ‘be’ Black girls and to grow into happy, healthy, and whole Black women.

GC: Though Black women and girls excel faster than any other subgroup, we still have difficulty navigating higher education and our respective careers. For me, transitioning from undergrad to graduate school and then to medical school was an arduous journey. Once again, having a Black female teacher was critical in helping me navigate the pitfalls of medical school. One of my medical school professors Dr. Millicent Channell, a Haitian American family physician, became my mentor and now friend. My relationship with her felt nostalgic of that with Dr. Watson. With Dr. Channell, I experienced feelings of trust, empathy, and someone who is present with presence. For me, this is why a mentor-mentee relationship between Black women and girls is critical in creating future leaders.

Based on my experiences, I believe that having Black teachers and mentors helps prepare students to succeed in a diverse society. For this reason, I want my children to experience diverse teachers, with an emphasis on Black teacher-mentor relationships. I want them to be comfortable at school with teachers that look like them and with whom they are able to identify. In addition, I want my children to be celebrated by their teachers, and I want them to be encouraged to do more with their lives. Like the many mentors I've encountered throughout my academic journey, I have taken up a mentorship role for Black girls at various points of their journey to becoming doctors and health professionals.

TW: My work as a teacher and now professor is rooted deeply in love. I love myself and I love Black people. Moreover, my love for Black people is not mutually exclusive. Meaning, my love for Black people does not negate my love for white people or for all people. It is quite the opposite. Because I love Black people, I am able to love all other people.

GC: As a Black woman who has similar experiences to the Black girls that I mentor, it is important for me to share my story, to be supportive, empathic, and to invest in their journey. It is my belief that it is important for them to learn from this mentor-mentee relationship and, in turn, when they have achieved relative success, become mentors themselves to other young Black girls. If we want to see a world with more Black women in leadership roles, we must take on the task of nurturing future leaders.

TW: I always tell my students what Toni Morrison told her students:

“When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.”